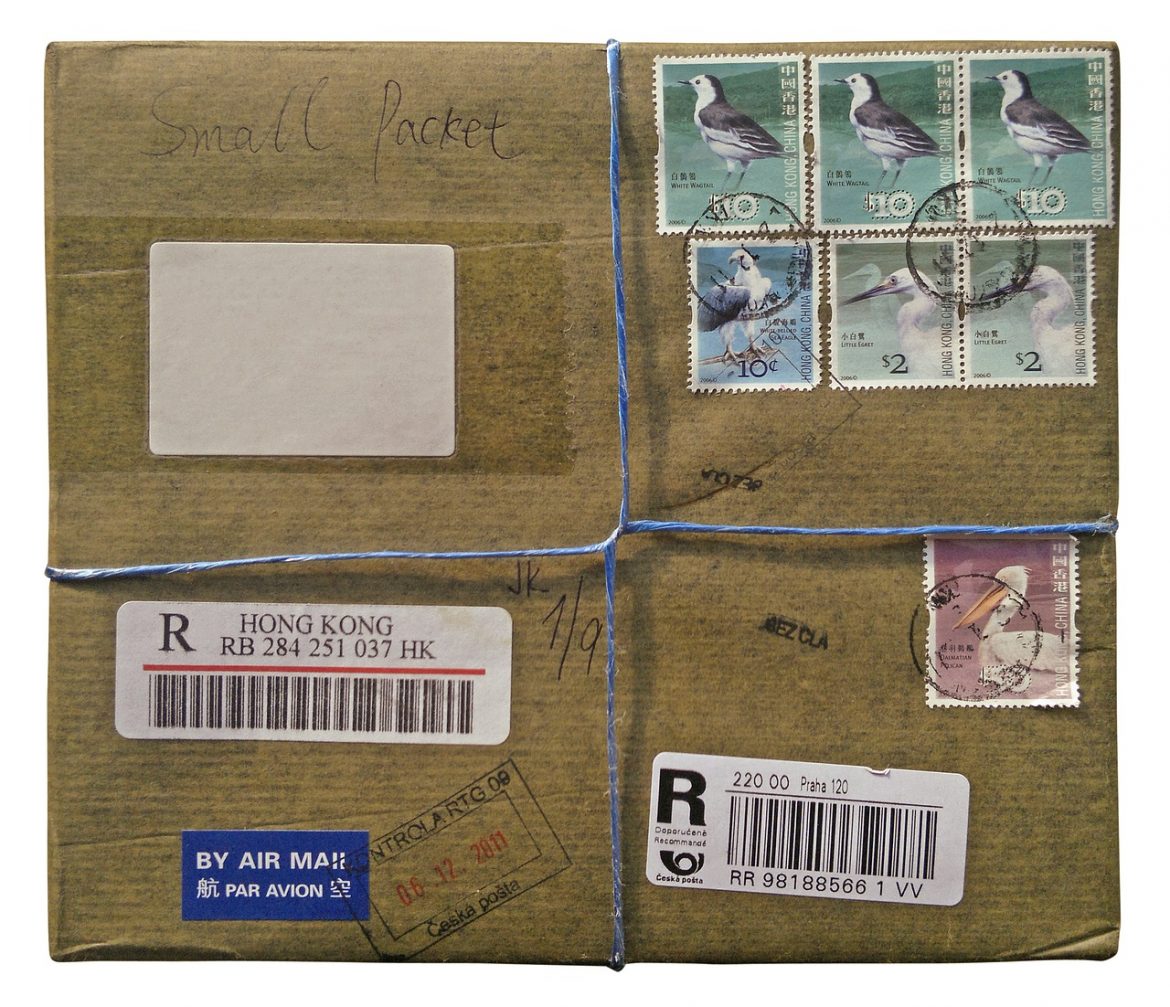

According to a recent report by the German news site Der Speigel, the NSA’s elite hacking division, known as Tailored Access Operations or TAO, has worked with the CIA and FBI to intercept and install surveillance software on laptops ordered by certain targets. This process, called “interdiction,” involves diverting the shipments to a secure facility, installing special software, then repackaging and sending the devices to their final destination. While Fourth Amendment protections might not apply to these packages once they leave the country, the seizure and reconfiguration of consumer products by the NSA is a significant privacy intrusion. These operations, if they were to take place within the United States, present two interesting Fourth Amendment issues that are not commonly discussed: the protection afforded to commercial packages in general, and international packages specifically.

Presumably these operations would take place within the United States prior to international departure. (If the NSA is using interdiction to infect laptops bound for domestic destinations, that would pose other significant Constitutional problems.) This raises the question: can NSA (or FBI) intercept and infiltrate these packages without a warrant? The answer depends, in part, on where and how the packages were searched and infiltrated.

Border searches can in many instances be conducted without a warrant, probable cause, or even reasonable suspicion. In United States v. Flores-Montano, 541 U.S. 149 (2004), the Supreme Court affirmed a “narrow” border search exception to the warrant requirement of the Fourth Amendment, grounded in the government’s right to protect the nation’s “territorial integrity.” And the Ninth Circuit recently held that commercial sorting facilities, like those used by FedEx to route international packages, are the “functional equivalent” of the border for purposes of this exception. United States v. Seljan, 547 F.3d 993 (9th Cir. 2008).

But the border search exception is not unequivocal, as the Ninth Circuit recently made clear in United States v. Cotterman, 709 F.3d 952 (9th Cir. 2013). In Cotterman, the court held that a comprehensive and intrusive “forensic examination” of laptops and other digital devices at the border requires reasonable suspicion. This is in line with the Supreme Court’s recognition in Flores-Montano that certain “searches of property are so destructive,” “particularly offensive,” or overtly intrusive that they require particularized suspicion. The Supreme Court just dismissed the petition to review Cotterman, so the forensic examination test is now the law of the Ninth Circuit.

A seizure and subsequent infection of a laptop with sophisticated surveillance software is clearly the type of destructive and overtly intrusive action that should require particularized suspicion under this analysis. But this presents another wrinkle: the role of the commercial carrier (FedEx, UPS, etc) in the interdiction process. At least one federal appellate court has held that the “right to inspect” outlined in FedEx’s terms of service agreement eliminated a sender’s reasonable expectation of privacy in the contents of their package. United States v. Young, 350 F.3d 1302, 1307 (11th Cir. 2003). Alternatively, the court held that the “bailment” relationship created by the shipment authorized FedEx to consent to a search of the package. Id. at 1308. But this logic has not been broadly applied in other circuits, and there would be significant implications for everyday FedEx and UPS users if it were broadly accepted.

But even under the Eleventh Circuit standard, I think the TAO interdictions described by Der Speigel would still be considered Fourth Amendment searches. First, because even though FedEx may reserve certain rights to inspect the packages it carries, that would not extend to the type of intrusive software infiltration involved in the TAO operations. And second, because the operations are initiated by NSA, rather than the commercial carrier. In United States v. Jacobsen, 466 U.S. 109 (1984), the Supreme Court affirmed that “letters and other sealed packages are in the general class of effects in which the public at large has a legitimate expectation of privacy; warrantless searches of such effects are presumptively unreasonable.” Id. at 114. The Court held that the search in Jacobsen was reasonable because the private carrier initially searched the package on their own, without the government’s involvement.

Interdictions have significant Fourth Amendment implications, even if they are limited to targeted international shipments, because they go far beyond what has traditionally been allowed under the border search exception. Furthermore, they implicate the rights of not only the customers, but also the vendors of these devices.

For more information visit www.EPIC.org. Defend Privacy. Support EPIC.